This report examines some of the historical, operational and psychological factors that prevent media firms from fully monetizing their information. It also explains the three ways that companies can turn data into cash. Finally, it will describe in detail—with leading-edge examples—eight strategies that media companies can use to rethink their approach to data and improve both operations and profits.

In short, this report outlines a new blueprint for monetizing media data that is tailored specifically for executives in video, film, music, publishing, marketing, advertising and social media.

The digital era has disrupted every industry, but none so thoroughly as media. Traditional broadcast, film, music and publishing companies have all had to re-invent themselves as digital creation and consumption became the norm. And newer media companies in the pure digital, social and mobile spaces have arisen only to be threatened by even younger ones a year or two later.

As players in an industry founded on information, these companies have long understood the value of data. In this hour of need, many have placed strategic data firmly in the C-suite, by appointing a chief data, revenue or innovation officer charged—in part—with making smarter use of information to drive profits.

But is the media industry really getting full value from its data? More specifically, is your company well positioned to gather, analyze and act on the information it generates—either to improve business decision-making or generate new income?

This report—based on research by FOLIO: Magazine, the leading source for strategy and insights in digital publishing, plus interviews with leading data experts—was created to answer those questions.

A rich vein, only partly mined

All companies generate data as a consequence of their normal business activity, but media data is unusually valuable.

That’s because it measures one of the scarcest and most elusive of all prizes: human attention. When social scientist Herbert A. Simon pointed out in 1971 that “a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention,” the data explosion had barely begun. Today, the overall quantity of information more than doubles every year. Media consumption is increasing, with consumers increasingly chasing desired content across multiple channels. And all of us are under constant assault by media and media-like communications from our screens, speakers, phones, watches, cars, appliances and more.

Vast sums are spent, in this attention-strained economy, to learn what we think; examples range from consumer marketing studies to political polling during election seasons. Yet simply by knowing what people are reading, watching or listening to, a large multichannel media company can learn more than all the marketers and pollsters combined about what really motivates people and the economic decisions they make.

Moreover, thanks to the growth of digital distribution, this information is increasingly collected at the individual level and in real-time—both key elements in boosting data value.

“People spend so much time with media—because they are constantly exposed to it—that the richness and volume of media data make it a highly valuable business resource,” says Anne Moxie, a senior analyst at Nucleus Research, a leading provider of case-based quantitative analysis for financial and technology decision makers. “Smart media companies should be calculating their ROI on that data, just as they would with any new content or show.”

Most media companies consider themselves well down the road toward realizing their data’s value. But is that so? This report’s look across the various media sectors suggests that, even at firms that place a premium on information, there are often roadblocks to realizing full data value based on the history and structure of the industry itself.

Media industry obstacles to smart data use

Because they deal in information, media companies are essentially engaged in a battle of ideas. That makes them highly vulnerable to competition. Anyone with a fresh idea, an appealing story line or an infectious beat can jump into the game and score—at least in theory.

During the pre-digital era, many would-be competitors were excluded by cost—partly of content creation, but even more so of distribution. It was prohibitively expensive to reach millions of people with a television broadcast, say, or printed copies of a magazine or newspaper. That favored the rise of giant networks, record companies, publishing houses and others that had access to large audiences, and thus could monetize content efficiently. Digital didn’t eliminate those barriers entirely. But it did flatten them, and enabled the rise of the micro-competitor—the influential blogger and the YouTube star.

One advantage that large media companies retain, however, is their ability to gather data about attention and consumption patterns of large numbers of people, across multiple channels and numerous media brands.

In principle, this data ought to give them a commanding advantage. Even in industries like video, film and music, where content is often licensed, distributors still own information about when, where, how, and why the content was consumed—and retain that ownership long after the license expires. That data should help them understand why the content succeeded (or failed) as well as what types of new content would be most profitable in the future.

In practice, many media companies fall short of that ideal—not through any fault of their own, but because they are held back by certain historical, structural and psychological factors that limit data valuation in this industry. FOLIO:’s research identified at least five such factors, which are listed in the box below.

They range from the industry’s hypercompetitive history to its penchant for traditional statistics and data siloes. But they are remarkably similar across various sectors of the communications industry. And all pose formidable hurdles to monetizing media data. Thus, the next two sections of this report will outline how to convert data into value and the specific strategies media companies can use to do so.

Five Obstacles to Monetizing Media Data

Even smart, successful media companies may be held back in realizing their data’s value owing to deeply ingrained habits, analytic methods and approaches to data that are common across all media sectors. Folio’s review identified five such factors that affect film, video, digital, print, and audio companies:

- A “lone wolf” mentality. Because they are fighting for a strictly limited quantity (attention), media firms typically wage a go-it-alone battle with competitors. Historical examples include the early film studios and big city dailies. Even today, big media firms fight ruthlessly for content, talent, and other advantages. But with data, this attitude can be detrimental—since most competitors are also potential data allies.

- Siloed data sources. Most media companies still draw information from legacy systems that do not communicate well. That makes it harder to develop a complete picture of the market—and get full value from their data.

- The splintering of audiences. Big media companies used to rely on scale to attract content, audience and advertisers. Today, their size pales when compared to digital giants like Facebook and Google, and even large audiences like those are valued mainly by how finely they can be sliced. Successful shows and publications aim not for giant scale but for a solid niche. And advertisers no longer buy “audiences,” they buy individuals.

- The atomization of the industry. The proliferation of distribution channels and lowered barriers to entry have weakened large vertically integrated media companies in favor of firms that excel at one link of the chain. That makes it harder for any single player to collect all the data it needs.

- Traditional attitudes towards “data.” Finally, because the industry has use data for so long, its view tends to be narrowed by long-standing benchmarks like ratings, plays, issue sales or ticket purchases. These numbers remain important, obviously. But they can obscure the potential of aggregated data that would reveal the underlying market forces driving such top-line metrics.

How media companies can monetize data

To overcome these obstacles, media companies should start by defining the specific type of value they hope to gain from their information. In general, smarter data management can add value to an organization in any of the three following ways. It can:

- Improve strategic decision-making. Most media companies begin their journey to smarter data management here. They seek better information to help them produce more appealing content, improve cross-promotions, boost customer acquisition, and the like—and have done so since the industry’s origin. The value of data emerges solely as gains in efficiency or profitability of the company’s existing functions.

- Attract and retain advertisers. Media companies have also long used “audience” data to lure advertisers, but the digital era raised the bar sharply. As noted in the earlier box , digital advertisers no longer buy audiences, they buy individuals—or thin slivers of audience based on individual demographics, content preference, purchase history and so on. The ad tech industry arose in part to meet this data need because media firms could not supply it. Today, media firms appreciate ad tech’s ability to fill unsold inventory. But they resent the fact that ad tech companies know so much about their visitors—and that the industry claims perhaps 50 cents of every advertising dollar. So many media firms now also offer their own proprietary data in an effort to provide advertisers a higher ROI while charging more for inventory and staying closer to sponsors.

- Direct revenue generation. While most media companies are active in the two areas above, relatively few have taken the next logical step: using data to create new information products that can be sold or bartered. Yet this option can be highly profitable, and as the most direct way to monetize media data has already proved a winning strategy for many B2B media companies.

The hitch is that none of these methods can unlock data’s full value unless the media firm approaches them the right way.

To understand the elements required for success, FOLIO: studied a number of media companies that have already executed profitable data strategies. We talked to key decision-makers about what they did and why it worked. That helped us identify eight key strategies that media companies can follow to get more value from their data.

8 Strategies to Boost Data Value

1. Treat data as product, not by-product

Most media companies think of data as an ancillary result of their operations—more or less the “exhaust” from their business engine. They monitor it for help in fine-tuning the engine and package it for presentation to advertisers. But it remains a by-product of their real concern, which is creating and/or distributing content.

Smart media companies are beginning to treat data as product in its own right. And that makes sense. No matter how data is monetized, it contributes to the top and/or bottom lines—and thus has value. The aim of the company’s data strategy should be to maximize that value.

A good first step is to inventory and formally value the data the company already posses, just as a retailer might value its inventory or a film company its vault. Gartner analyst Douglas Laney recommends such an approach in his study Why and How to Measure the Value of Your Information Assets. Laney blames “archaic accounting practices” dating back to the postGreat Depression era for the fact that this is not a part of normal accounting procedure, even though accounting rules do permit companies to value other intangible assets like copyrights, trademarks or patents. Laney estimates that nine out of 10 business leaders consider information a strategic asset, yet fewer than one in 10 try to assign it a value. But the study also says that perhaps one-third of companies are now trying to monetize their data directly, either by selling it to other firms or using it to barter.

FOLIO: is in regular contact with one large East Coast-based B2B publisher that has pursued this strategy aggressively. Like many industry-focused publishers, this company—which cannot be identified here for competitive reasons—has its roots in a broad portfolio of trade publications plus events, guides and the like. But as advertising demand shifted from print to online in recent years, the company found itself looking for ways to boost digital revenue.

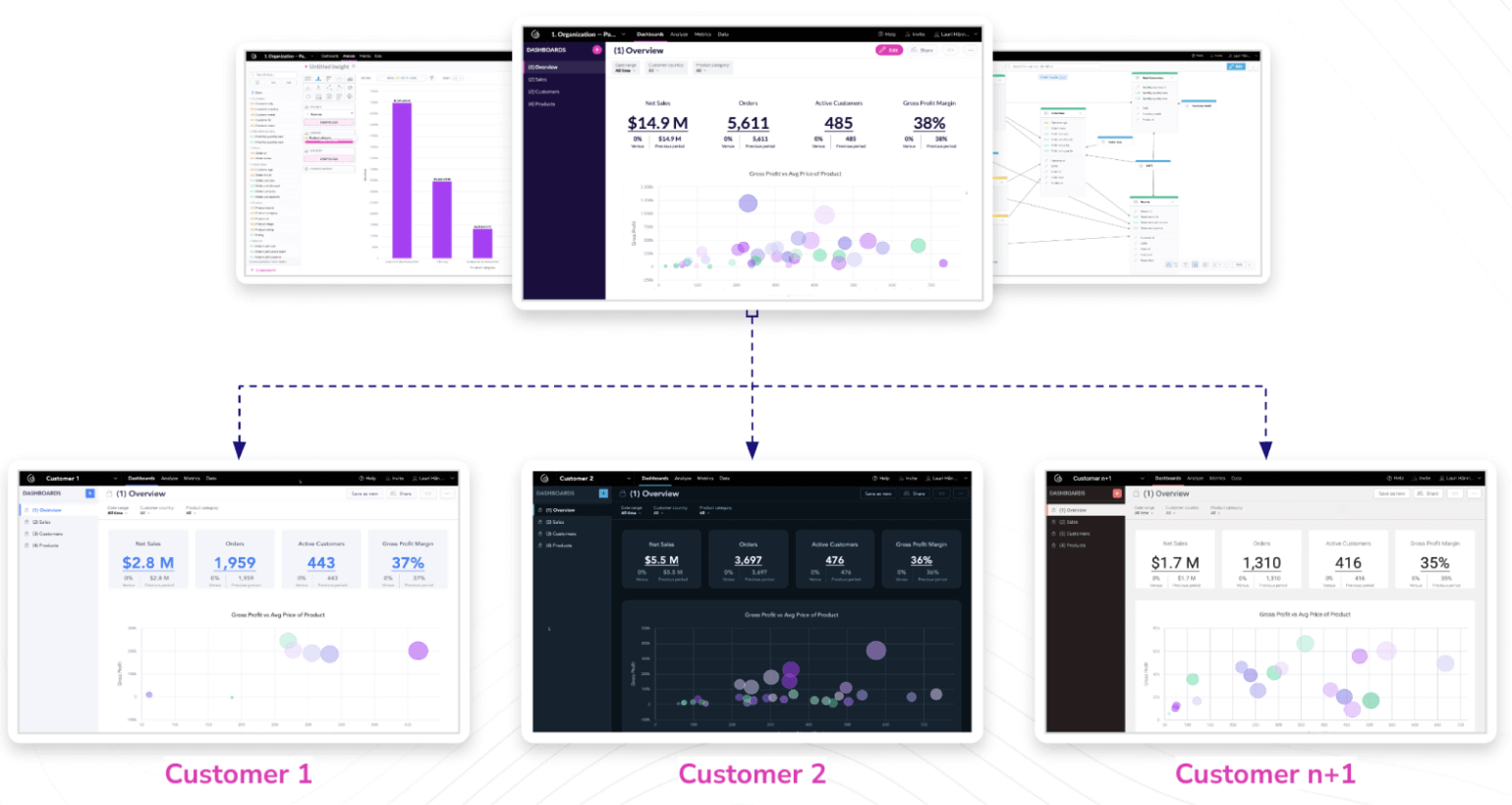

The solution? The company used its deep knowledge of the industries it covers to reinvent itself as a distributive market intelligence company, with verticals in key industry areas. Each of these verticals—powered by GoodData—is a well-designed subscription-based data product that provides industry-critical information with actionable forecasts. To create these, the company combined information from third-party sources with its own deep insights gleaned from a client list that includes up to 85 percent of all U.S. GDP in the market sectors it covers. Thanks to that deep data store, the publisher can now deliver predictive market analytics that enable clients to improve their own projections, hone marketing, create new products and boost sales. And that, in turn, has generated new digital revenue for the publisher while creating spillover profits in other areas, such as conferences and digital publishing.

While B2B companies have been at the forefront of this movement, in principle the same strategy could be employed by any media company with deep visibility into an important market, such as autos, beauty, entertainment, or fashion. The key is to stop thinking only about how data can help your company. Think instead about how it could help other companies that would pay or barter for it, and then look for ways to improve that data as outlined in our next strategy.

2. Re-define what information you need

Once companies get used to the idea that data has intrinsic value, they are in a better position to recognize what data they do not have—but need. Indeed, the data experts we spoke to described this as the next step in a wellplanned data overhaul. Once you have inventoried the data your company has, then ask what other information—internal or external— would add value for your company, its customers or partners.

The value of data as a competitive differentiator stands out clearly at a company like Invodo. The Austin, TX-based firm specializes in a single, distinctive media niche: streaming product videos that retailers and manufacturers use to sell products online. But within that field, it has raised data collection to a fine art, generating insights that larger video companies, including broadcast networks, may want to emulate.

One foundation of Invodo’s business, as Senior Product Manager Eliot Towb explains, is high efficiency video creation. The company maintains a 33,000-square-foot studio north of Dallas where products are warehoused and shot for Invodo customers.

The other part of the company’s business involves hosting and analyzing these videos when they are streamed from retailer websites. “With a product video,” Towb explains, “you’re not trying to create a commercial. Instead, you want to educate the customer on the features and benefits of a given product so they either decide to buy it, or decide it doesn’t work for them and choose a different model. The goal is to increase customer loyalty, site stickiness and, ultimately, conversion.”

In that context, Towb says, many conventional video metrics turn out to be misleading. For example, most media companies try to persuade viewers to watch a stream all the way to its end. But Invodo has found that, with product videos, some of the best ones are abandoned mid-way through because the viewer finds out everything he or she wants to know. And even product purchase—the ultimate goal of such videos—is not, by itself, a complete measure of success. Invodo has shown that good videos also help viewers choose which products they do not want. So a successful video may actually steer a visitor away from a given product towards one that better meets their needs. “That means you will have fewer customer service calls and returns, which is also a win,” says Towb.

The key to insights like the above lie in two streams of data. First, Invodo collects actual purchase results from the retailers that use its hosting platform, and then maps that data back to individual viewing history.

Second, Towb says, with every video stream, Invodo invites the viewer to rate the video with a “satisfaction” metric that lends depth to its analysis. “While the video is playing, we prompt the user to leave a rating on whether it was helpful, and we also prompt for a comment,” Towb says. That helps the company understand which videos are really working and why, and has led to many innovations that boost video effectiveness.

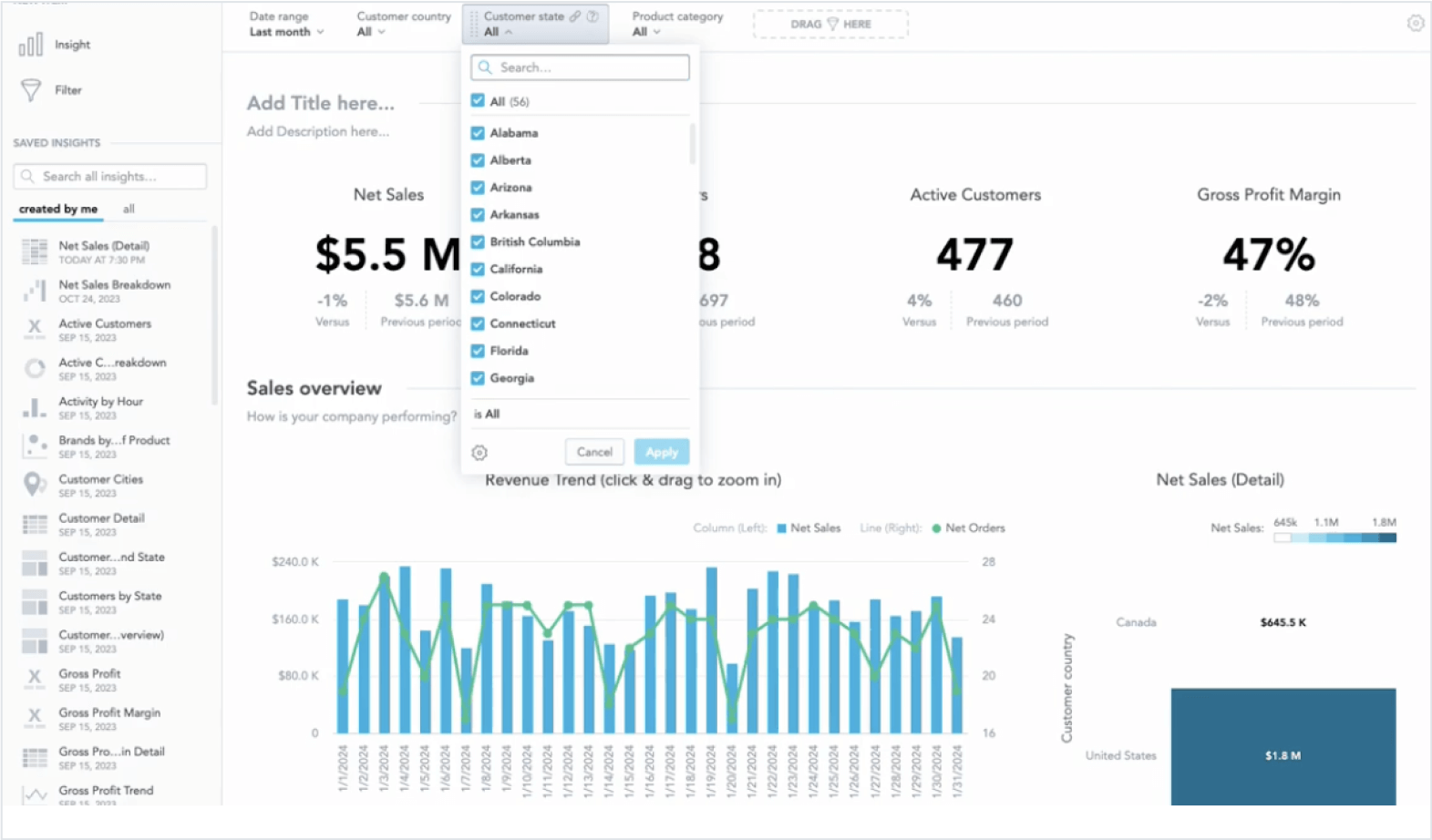

Using the GoodData platform, the company makes this information visible to both internal stakeholders and retailer clients. That way, the retailer can see for him- or herself the impact videos have. Through A/B testing, Invodo can also calculate for each customer the actual ROI on its video investment—meaning the incremental revenue the client earned by including video for a product, even after accounting for any visitors who arrived at the site with pre-existing purchase intent.

By establishing a baseline average “lift” in sales, and using the client’s purchase data for all products, Invodo can suggest what additional products the customer might want to consider for video. It can even estimate the likely additional revenue, thus enabling a category-bycategory or even product-by-product analysis of the ROI of new video production.

Though Invodo operates in a highly specialized niche of digital media, these benefits would be immensely valuable to conventional media companies seeking to attract and retain sponsors, for example. And they come from thinking creatively across a large partner network about what kinds of data would add value for all.

3. Integrate your data sources

In order to use your company’s data, you must be able to see your company’s data—ideally all in one place. And there, media companies run into the same obstacle that many other industries face: the fact that their information is scattered across a number of siloed, legacy data systems.

Some media companies have tackled this problem by rebuilding the entire data-collection and storage stack, relying heavily on in-house hardware and software. That solution allows a high degree of customization, but is typically expensive; takes a long time to roll out; and is difficult to alter later as circumstances in the media market change, which, as noted earlier, can happen at light speed.

Thus, other media companies have chosen to use an outsourced, cloud-based solution instead. This approach offers as much flexibility as an in-house solution but can be implemented faster, uses existing data sources, costs less, and can be revised on the fly as conditions require. In a typical scenario, the media company might continue to collect information using its existing legacy mechanisms. But it would combine that data in a cloud-based, visually-oriented analytics engine that normalizes and integrates the various information streams and pumps them out to both data scientists and business users.

The advantage of this approach is that it is source-agnostic: the cloud-based system can tap data not only from existing legacy sources but from new ones. That could include upgrades to your in-house data collection mechanisms, which would result in a more detailed picture of the business. It could include information from suppliers, customers, data partners and third-party sources. And if the system is simple and intuitive to use, then its tools can be made available to business users—not just those with expertise. That helps reduce workload for the IT and data analytics teams, while keeping the services firmly under their control.

GoodData’s Services Data Product team has worked with many media clients to implement such solutions, including one company that— though it cannot be identified here—is a major broadcaster operating both in the U.S. and globally. Members of the data team at this customer found they were spending too much time integrating data manually—often by cut-and-pasting it into spreadsheets. So the team was looking for a scalable system that could handle the company’s diverse digital business information streams, which numbered in the hundreds.

With assistance from GoodData, the analytics team launched a series of executive dashboards in less than 90 days, and then gradually expanded its offerings to cover both domestic and international business, plus data from third-party sources and partners. Eventually, more than 100 employees worldwide were using the analytics tools. That freed the data analytics group to devote more time to substantive strategic analysis, which enhanced the strategic value of their work.

4. Look beyond company walls

In the technology industry, it is commonplace today to share proprietary information with partners to increase collective profitability. Technology manufacturers, for example, routinely share data like their sales forecasts and projected needs with suppliers, and vice versa, so everyone in the supply chain can adjust smoothly to changing demand.

In the media industry, this practice remains rare—thanks, among other factors, to its relatively loose supply networks and traditional “lone wolf” mentality. But FOLIO:’s research turned up numerous examples of how data sharing can be every bit as profitable for media as for manufacturing. Invodo, for example, pulls in secret, proprietary sales data from its retailer clients and feeds back aggregated information that helps everyone make more money.

Often, the impediments to sharing have little to do with today’s market, and everything to do with legacy attitudes. That was the case when GED Testing Service, the company that has long offered high school equivalency testing, updated its reporting services two years ago.

The company, a joint venture between the American Council on Education and media giant Pearson, is selected by states to support high school equivalency testing. It has contracts with individual states, which often recruit and fund students.

Though lnvodo operates in a highly specialized niche of digital media, these benefits would be immensely valuable to conventional media companies seeking to attract and retain sponsors, for example.

And they come from thinking creatively across a large partner network about what kinds of data would add value for all.

For many years, GED Testing had aggregated these test results in a legacy data system and published them as a printed Annual Statistical Report (ASR) that was distributed to clients each May. The ASR was widely followed, since it helped state education officials compare their results to those of other states and the nation. By the late 2000s, however, the ASR had fallen behind the times. It could not accommodate the huge trove of demographic and test data that GED was collecting. And, thanks to the once-yearly schedule, it was perpetually out of date.

To solve this problem, GED Testing first set out to update its storage. The company considered investing in a $2 million on-site system, but eventually decided instead on a cloud-based GoodData solution that was faster, more flexible and less expensive. That made it possible to put powerful and continually updated data analytics tools directly in the hands of internal users like Operations and Marketing, says Sarita D. Parikh, Senior Director of Technology and Operations at the company’s Bloomington, MN office.

The next step was to offer similar capabilities to the states, and phase out the annual publication. “There was considerable wariness in the market about not getting a booklet,” Parikh remembers, “but the first time we did a demo of the new system for anyone, their jaw dropped.”

The new analytic tools allowed state officials to peer deeply into near real-time data from their own and national tests to evaluate their programs’ effectiveness. It also helped them look good when the governor’s office would call late Friday afternoon asking for some special data request. “Prior to the upgrade, that could mean an all-weekend fire drill,” says Parikh. “Now they can just print out a beautiful report and send it over.”

Thanks to such services, GED’s transition from printed ASR to on-demand analysis turned out to be easier than expected. “We sent out a PDF version of the annual booklet for 2015. But in 2016 we did not even produce one, because the market was so acclimated to on-demand analysis,” says Parikh. Now GED’s problem is not persuading stakeholders to use the tools, but keeping abreast of their incessant demands for more. “Data is like money,” Parikh observes. “The more people have, the more they want. But that just means we have a really engaged customer base, and can consider which of the proposals would be most valuable across the network.”

For media companies, the lesson is that while your customers and partners may be reluctant to share data initially, the mutual benefits of a well-constructed network will soon wear down resistance. So in re-thinking your own data strategy, be sure to look outside company walls. Consider what data might benefit the entire ecosystem of content creators, distribution partners and advertisers. Then initiate discussions to get them on board.

5. Spread access generously—but securely

One common theme from all the data experts we queried was to share analytic tools with as many potential stakeholders as possible, including lower and mid-level decision makers who are often the last to benefit from such plans.

This advice runs counter to the typical practice at media companies, which usually begin with executive dashboards and tightly controlled access. The advice may also seem counter to data managers’ own self-interest. IT executives may be reluctant to outsource key functions to cloud-based services. And analytics experts may worry that sharing data tools will make their skills less vital to the organization.

In fact, as Invodo, GED Testing and others have discovered, the opposite is true. Sharing makes IT and analytic teams more valuable, not less. It stops them from serving as data “go-fers,” and helps them spend more time working on important strategic decisions. Moreover, as access percolates down through company, the new users come up with ideas for improvement. That makes the whole system more valuable, and the analytics team goes from being an on-call information retrieval service to enabling company decision-making at all levels.

To succeed, however, data sharing must include superior security. This is particularly important in the media industry, with its historical competitiveness. And it comes into sharp focus when the network includes partners who are competitors, either with each other or with the media company itself. Retailers in the Invodo video network, for example, would never share sales numbers if they feared the data could leak to a competitor. But once the system is secure, all players benefit hugely from the aggregated and anonymized sales-data pool.

6. Go beyond information to insight and action

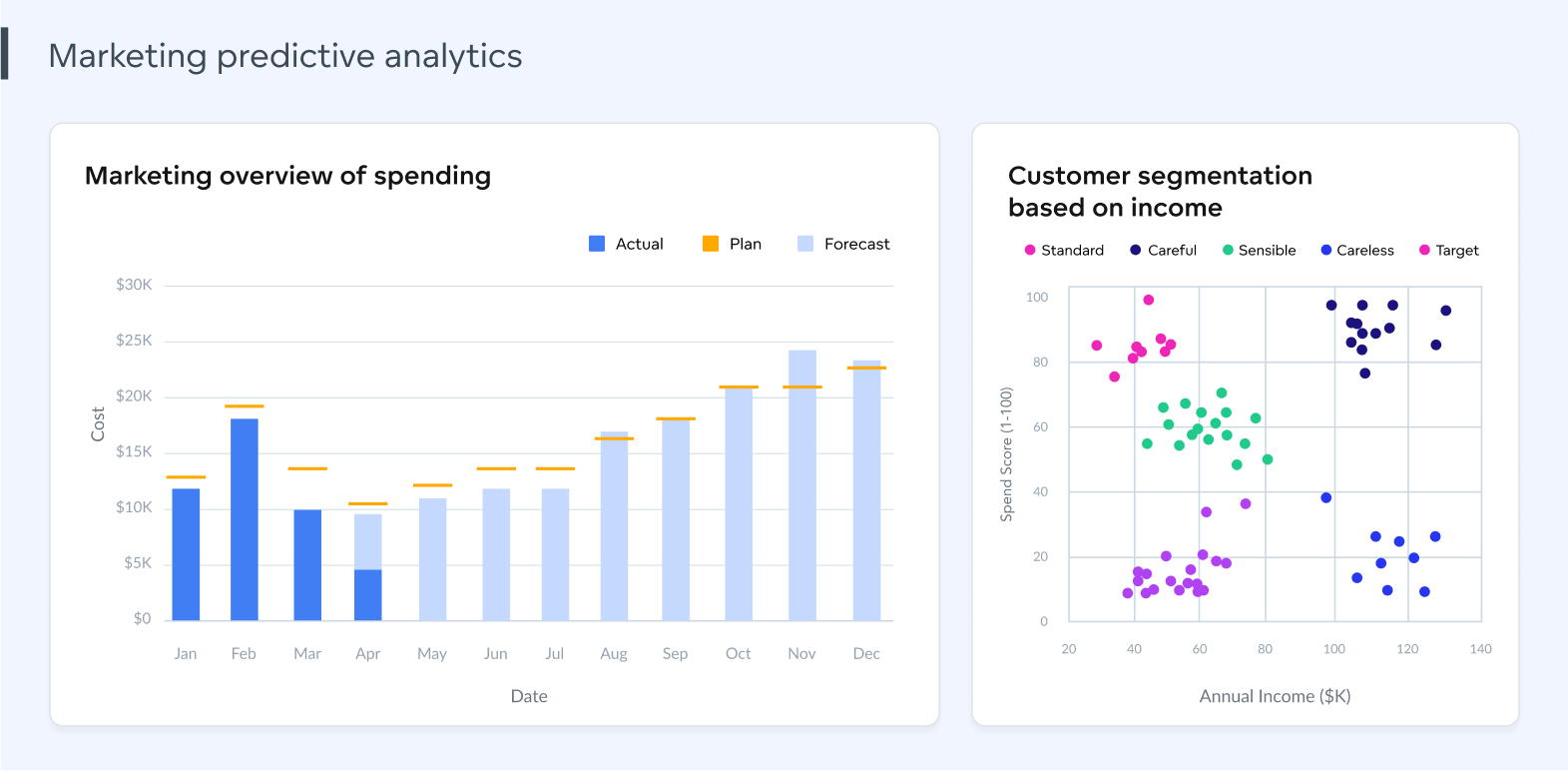

Data in old-style media was usually backward-looking: last night’s viewership, last month’s sales. To a degree, that’s still true. But smart media companies increasingly treat information as a forward-looking resource—something that exists to drive future behavior.

This shift—from traditional business intelligence (BI) toward predictive and even prescriptive analytics—can be highly profitable. A recent study by Nucleus Research, the Boston-based firm that specializes in ROI analysis, found that advanced analytics solutions yield 2.2 times more ROI than traditional BI products, since they allow company managers to anticipate and prepare for change. “That is particularly important for media companies because the industry moves so quickly,” notes Anne Moxie, the author of the report titled Advanced Analytics Delivers 2.2 Times More ROI. “Most industries don’t move that fast and don’t need that kind of flexibility. But media is an entirely different beast.”

You can see the value of the predictive approach at Twitch, the social video network for digital gamers. While the San Francisco-based company is still known best among gaming enthusiasts, it represents an excellent model for a next-generation media company. As Jenny Qian, director of business operations puts it, “At Twitch, every decision we make is heavily influenced by data.”

Today, Twitch is the gaming industry’s media powerhouse with nearly 10 million daily visitors and 2 million streamers per month. The average visitor watches one-and-three-quarter hours of video daily. And at peak times, like when gaming companies stage massive multi-team tournaments, it can be the fourth highest-trafficked site on the Internet, with shot-by-shot commentary reminiscent of a Super Bowl.

The magic of Twitch is that it is also inherently social. The vast majority of content is still user-generated, though there are also commercially produced channels from game makers and Twitch itself. And its outsized impact on the gaming community has made it a cornerstone of marketing and promotion. Game makers rely on Twitch to link them to “influencers” who have a wide following. Then they sponsor the influencers to promote their products—like a shoe company backing an Olympic runner, or an auto maker branding a NASCAR driver.

The difference is that, with Twitch, the visual and financial impact can be measured on a click-by-click basis, and that’s where Twitch’s data experts come in. Drew Harry, who runs the data science team, aims to make “evidence-driven decision-making a central part of how we build great products”, as he put in a recent blog post. And Qian’s Business Operations group provides special support to top management. “We think of ourselves as internal consultants,” she explains. “We use both internal and external data to help answer big questions, like what country Twitch should expand into next, or what features should we add to stay ahead of the competition.”

This plethora of data has led to many insights. For example, despite the lengthy average viewership, Harry’s group has found it most helpful to quantify viewing in five-minute segments that function like a single “quantum” of attention. That enables them to draw maps of gaming behavior that show considerable overlap among fans of the various games. Thanks to such studies, Twitch probably has the broadest view in the industry of what gamers really like at any given moment. And the data show that those preferences can change instantly. For example, 40 percent of visitors who “follow” a gamer’s channel do so within the first minute of viewing. So by tracking viewing and social behavior, the Twitch scientists not only produce a snapshot of activity at any given moment but—in some cases—can anticipate where viewer tastes are going next.

The lesson for other media is to approach data not just as a measure of past results but as a trigger for future action. In some cases, the actions may be outward facing, as with subscription data products. But at most companies, they will be internal. Company stakeholders will come to rely on data to drive decisions, as they did at Twitch, including some that may become partly or fully automated. Whatever the specific outcome, the company will have stopped thinking of data as something that belongs only to the past.

7. Play to your strengths, plug your weaknesses

No company can do everything well, and media companies in particular are good at managing endemic technologies and less proficient beyond that. So once your company has settled on the key elements of its data strategy, the next step is do an honest appraisal of capabilities. Which parts of the strategy can the company execute on its own. Which parts will require new expertise or even outside partners.

Typically these discussions come down to some form of the “build vs. buy” dilemma. That was the choice GED Testing Services faced when modernizing its data systems (see Strategy #4 above). In that case, the decision to partner was driven by a desire to control costs, accelerate time-to-market and maximize future agility. But more generally, says GED’s Parikh, companies should consider the opportunity cost of building in-house. “Sometimes, that can be like bringing in a giant backhoe to dig a hole for a bush at your house,” she says. “You need to think about what that project will prevent you from doing that could be more strategic.”

For media companies, the message is to concentrate their energy on activities that only they can do and that add the most value. Sometimes that means embarking on a huge new building project. But in many, perhaps most, instances, it means plugging their technology gaps with carefully chosen partners.

8. Move fast, even if you start with baby steps

Finally, a piece of advice that may seem obvious but cannot be stressed enough. At its outset, this report observed that no industry has been so disrupted by the information technology revolution as media. There are many ways to measure that disruption. Traditionally, the industry was headquartered in large population centers like New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington, Atlanta and so forth. Today, the biggest “media” companies are on or near the San Francisco Bay, thanks to its concentration on technology. And even leaving geography aside, no one expects the pace of technological change to slacken—nor any lull in the rapid evolution of consumer media tastes.

So for media companies in particular, speed to market is critical. At some companies, especially large ones, that pressure can be fearsome. The scale of investment makes executives feel they must make exactly the right decision the first time, or their data investment will be misspent. But—as in the technology industry—that caution can lead to missed opportunities and the need to play catch-up with competitors.

This challenge emerged as a common problem in our conversations with media data executives, but so did its solution. Most successful companies, it turns out, start re-building their data systems with very tiny steps. They tackle the problem iteratively, rather than all at once.

The point is that, as with tech, media data projects move fastest when they start small. Consumer habits, the competitive landscape and the underlying technology change too rapidly to justify giant bets. Instead, smart executives start by doing something that is strategically sound but fast and affordable. Then they use the lessons from that rollout to inform their next move, and then the next, and so on.

Conclusion:

As the strategies above show, getting full value from media data requires adopting a new process—not just achieving a one-time goal. Smart companies start by evaluating their own internal obstacles so they can approach the problem correctly. They then conduct a data inventory and evaluation to understand the value they have and what value could be added through additional data gathering or the addition of partners and customers to their network. Finally, they begin a step-by-step rollout that spreads access widely enough to have impact at all levels of the firm.

Media companies that follow this blueprint will find they not only realize greater value from their data today, but position themselves for future gains as digital technology continues to transform media for years to come.

Continue Reading This Article

Enjoy this article as well as all of our content.

Does GoodData look like the better fit?

Get a demo now and see for yourself. It’s commitment-free.